He was America’s most beloved deejay, the unmistakable voice who created ‘American top 40’ and rose to fame on the schmaltzy but irresistible charm of his “long-distance dedications.” all of which makes the tabloid circumstances of his demise—an epic family feud waged in streets, courtrooms, and funeral homes from L.A. to Oslo—even more surreal. Amy Wallace investigates the tragic final days (and very weird afterlife) of a radio legend

When Casey Kasem’s wife got angry, it didn’t matter that the old man couldn’t walk and could barely talk. When Jean Kasem felt possessive, it just didn’t matter that her ailing husband—the legendary deejay whose warm, husky voice had once reached a reported 8 million listeners in seventeen countries—couldn’t swallow and was at risk for aspiration. Jean was upset that Casey’s two daughters from his first marriage had dared to visit their father without her permission. Her will would be done.

It was after midnight on May 7, 2014, when Jean arrived at the Santa Monica convalescent hospital where her 82-year-old husband was suffering from Lewy body dementia, a disease similar to Parkinson’s. She told the nurse on duty that it was unacceptable that Kasem’s eldest daughters had come by the day before to talk with him and hold his hand. Jean said the facility offered “no privacy for Mr. Kasem,” according to the nurse’s sworn declaration, and therefore she was removing him immediately. The nurse told Jean that such a move could kill him. Kasem’s feeding tube, which was surgically implanted in his stomach, would require immediate medical intervention if it became dislodged, and Kasem’s doctor had refused to issue discharge orders.

Jean didn’t relent. At 2:30 A.M., the sometime actress—a zaftig blonde who once played Loretta, the wife of Nick Tortelli, on six episodes of Cheers—put her bedridden husband in a wheelchair and rolled him out into the night. It had been just five years since Kasem signed off on his final countdown, but to look at him, you’d think it might have been much longer. Frail and bewildered, he was loaded into a white SUV that was driven by a private caregiver. Jean and Liberty, her 23-year-old daughter with Kasem, piled into a different SUV, this one black, and sped away. Just over a month later, Kasem would be dead—and about to embark on a posthumous journey that would take him halfway around the world.

“This broad is right out of a Raymond Chandler novel,” Logan Clarke told me, referring to Jean and sounding like a man who’s read a few Chandler novels himself. Clarke, a private investigator whom Kasem’s eldest daughter retained to track Jean down, is one of several characters in this story who come across like some fun-house distortion of an L.A. stereotype. “The six-foot blonde wannabe actress ‘kidnaps’ the seriously ill star from the hospital,” he says, “and hides him from the world, with a private eye in hot pursuit.”

···

Sit back, close your eyes, and try to come up with an American celebrity, living or dead, you’d beless likely to associate with this kind of lurid tabloid grotesque than Casey Kasem. (Okay, maybe Mister Rogers.)

Long before America’s most beloved radio personality got sucked into the vortex of his family’s fierce infighting—before Jean barred his three children from his first marriage and his only brother from visiting him; before the battle spilled into court, racking up more than $650,000 in lawyers’ fees; before Kerri, Kasem’s eldest daughter, took custody of her father, prompting Jean to stand in a driveway hurling raw hamburger meat while quoting what sounded like Scripture; before various Kasem relatives accused one another of infidelity, of posing for pornography, of greed and lying and unimaginable cruelty; and before Kasem died in a Seattle-area hospital and his final chapter played out like a real-life Weekend at Bernie’s—thirty-nine years’ worth of weekend mornings began something like this:

Here we go with the top forty hits of the nation this week on American Top 40, the best-selling and most-played songs from the Atlantic to the Pacific, from Canada to Mexico. This is Casey Kasem in Hollywood….

His voice was unmistakable—richly nasal, with an unpolished quality that he dubbed “garbage” for its familiar guy-next-door tone. That, Kasem always said, was key to his popularity: He sounded like a regular Joe just telling a few stories. Except that the Detroit-born son of a Lebanese grocer was so much more than that. From 1970 until his final show in 2009, Kasem’s reports of which songs had leapt up a notch and which had slid down reflected a belief in meritocracy and a sort of Horatio Alger-style optimism that was peculiarly, iconically American. When he read a long-distance dedication, he imbued it with an intimacy upon which his listeners came to rely. It comes to us in the form of a letter: “Dear Casey…” Kasem was a constant reassuring presence that bound generations together. He was schmaltzy, sure, but classy, too. A reliable standard-bearer. A stand-up guy.

“Of all the radio personalities in America, Casey was the most significant, period,” said Mike Curb, a record executive and former lieutenant governor of California who was Kasem’s close friend for more than forty years. On his show, Curb said, Kasem “affected the culture of music and the importance of Top 40 music more than any person who has ever lived.”

Kasem got his start in the mid-’50s, voice-acting on Detroit-based radio shows such as The Lone Ranger before becoming a radio announcer in his hometown and later in Cleveland, Buffalo, Oakland, and Los Angeles. He and a few partners launched American Top 40 on seven stations in 1970; that number would eventually exceed 500. The four-hour weekly program was tightly scripted, with folksy admonitions, lessons in music history, and plenty of “teaser and bio,” a cliff-hanger technique that Kasem had developed while spinning records in the California Bay Area.(How did the B-52’s get their name? Find out after the break….) By the time ABC purchasedAmerican Top 40 in 1982, Kasem was reportedly paid more than $1 million a year for that hosting gig alone. He was getting rich in other ways, too: He was the voice behind NBC’s network promos (another $1 million a year), and he did countless ads and cartoon voices (most famously as Shaggy on Scooby-Doo) that brought in millions more. In 1989, he secured a five-year deejay contract worth $15 million—reportedly about the same as CBS was paying nightly news anchor Dan Rather.

This is about the time you’d expect to learn that Jean Kasem was a recently acquired trophy wife, a gold digger like, say, Anna Nicole Smith, who married a man sixty-three years older, then sought to collect a hefty chunk of his fortune when he died just thirteen months later. In fact, it’s a lot more complicated than that. Jean and Casey Kasem were closer in age—now 60, she was twenty-two years his junior—and they’d been married for thirty-three years at the time of his death.

They’d begun dating not long after Kasem’s first marriage ended in divorce. Casey was lonely then, longtime friends say; he hadn’t wanted to separate from the mother of his three children. “How many guys have we heard of who end up in a divorce that they don’t want, and then, on the rebound, along comes somebody who appears to think you’re the greatest thing on earth?” Mike Curb told me, recalling that Kasem and Jean met at Kasem’s agent’s office, where she was the receptionist. Jean disputes this, or so she told me when we met at her suggestion in a hallway at the Los Angeles courthouse. There she ominously called Curb “one of the accomplices” but refused to elaborate. However Casey and Jean met, they were married in December 1980, in a ceremony at the Hotel Bel-Air officiated by the Reverend Jesse Jackson.

In 1989, Casey and Jean moved into a 2.4-acre gated compound in L.A.’s ritzy Holmby Hills neighborhood. The estate has seven bedrooms, ten and a half bathrooms, a motor-court fountain built around an ornate piece of the Brooklyn Bridge, a hair salon, a par-3 golf course designed by Bobby Trent Jones, and a heart-shaped pool with two bathhouses. They paid $6.8 million for it, and last year it was briefly on the market for $42 million. Since Kasem died, his estate has been estimated at $80 million.

Hearing that, it’s natural to assume that Kasem’s elder kids are fighting with their stepmother and half sister over their father’s fortune. Not so, says Kerri. “We’ve never asked for it once,” she insists. The two sides are squabbling over a relatively small life-insurance policy, but there’s no real dispute over the bulk of Kasem’s wealth, most of which will probably go to Jean.

So where does all the hostility come from? It’s as if there’s never been a moment of peace between the sides—as if acrimony were simply the Kasems’ way of being. Who “started it”? Who knows. But the bottom line is that Jean Kasem and her stepkids disagree about, well, everything.

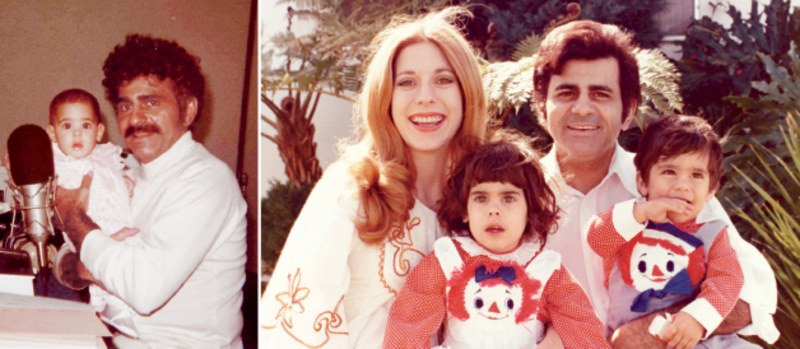

A tale of two families—or rather, one family hopelessly divided. From left, Casey and his first born, Kerri, in 1972; with his first wife Linda, Kerri, and Michael. Photos: Courtesy of Kerri Kasem

At 42, Kerri Kasem is striking, with long dark shiny hair and the lithe build of someone who eats sparingly, if at all. For decades, Kerri—an L.A. radio personality who has also been an MTV Asia veejay, a UFC host, a Maxim model, a bungee-jumping instructor, and an actress—was a vegan like her father. (Then her hair started falling out. She’s now a vegetarian.) Not eating meat was just one of many ways that she and her brother and sister—Mike, 41, and Julie, 39—connected to their father after their parents divorced, Kerri tells me when I meet her for breakfast in Los Angeles’s San Fernando Valley. “We loved our dad so much,” she says. Their stepmother? “She’s psychotic. And what she did to that man is unconscionable.”

According to Kerri, who was 8 years old when Kasem remarried, Jean couldn’t stand her stepchildren from the start. Kerri, Mike, and Julie came to the house every weekend as kids but never felt welcome. “She would do weird things,” Kerri says of Jean. “My dad would leave the room, and when he came back in, she would say we did or said something, so he would get angry.” On one occasion, Jean blew up at Kerri and several of her friends: “She goes, ‘Do you know what I fear? Liars!’ I remember her crazy-eyed.”

The kids and their stepmother barely tolerated one another for decades, but Casey still managed to maintain his relationships with Kerri and her siblings. Kerri remembers her father often trying to explain Jean’s behavior. “I knew he loved her,” Kerri said. “He’d say, “‘She’s insecure. It’s going to get better.’ One time, probably fifteen years ago, he said it again—’It’s going to get better’—and all of us, including him, started laughing. It was like: It’s not going to get better. It’s never going to get better.”

The kids were well into adulthood by the time their father started showing Parkinson’s-like symptoms in the mid-2000s. Still, Julie and Kerri visited with him almost every Sunday. (Mike, who now lives in Singapore, where he is a deejay, would join the family whenever he was in town.) But the visits were never at the Kasem mansion; Jean had made it clear the kids weren’t welcome there. Instead she would arrange for Casey to be delivered to Julie’s home, Kerri says. Then, in the summer of 2013, Jean put a stop even to those visits, in part because Jean said his deteriorating health prevented him from traveling. “She blocked us entirely from seeing Dad,” Kerri says. “Then she started spewing lies—that my dad had distanced himself from us, that we had borrowed money from him. Like: junk.”

By early October of 2013, after two months without seeing him, the kids grew concerned that Casey was not receiving adequate care. They organized a protest in front of the Kasem mansion, where about twenty-five people stood quietly holding handwritten placards. jean, why won’t you let me see my dad!? read Kerri’s sign, while Mouner Kasem, Casey’s 78-year-old younger brother, held one that said i miss my brother. Jean called the police, drawing several squad cars and a helicopter to the scene—and the next day, there were headlines on CNN, TMZ, and just about every news outlet in between.

In the ensuing months, Jean offered a deal: Her stepkids could see their dad once a month for an hour, but a security guard had to monitor their visits, and the kids would have to split the cost of that guard with Jean. They would not be allowed to have phones or any other electronics with them, presumably to prevent photographs or any communication with others.

“It was like a fucking jail,” Kerri says of Jean’s proposal. “I said, ‘I’m not signing any of this.’ ” Kerri’s siblings, however, weary of the constant battling and worried they might never see their father again, caved to Jean’s terms. “My younger sister and I had our reasons for throwing in the towel,” Mike tells me when I reach him in Singapore. “We said, ‘Okay, fine, at least we’ll get to see Dad.’ I just felt like, ‘I don’t have any more fight left.’ And then immediately Jean reneged.”

The elder Kasem kids did see their father briefly in December, when he was hospitalized, but soon Jean moved him again. By early May of 2014, they had no idea where he was; Jean wouldn’t tell them. Worried that Casey’s time was running out, Kerri’s lawyer informed Jean’s lawyer on May 6 that Kerri intended to file papers to seek temporary conservatorship over her dad’s care.

That same day, in a meta twist that only highlighted what a tabloid dream this story had become, someone from TMZ called Julie Kasem with a tip: Their father was living at the Berkley East Convalescent Hospital in Santa Monica. Julie, Kerri, and an attorney immediately drove over. The attorney had to cite a federal statute to be granted entry to Kasem’s room, but once they got inside, the lawyer wrote in a sworn statement later, what unfolded was a heartwarming scene: “When Kerri greeted her dad he responded by trying to talk, and his face lit up with as big of a smile as he can make…. It is hard to put into words how much joy Mr. Kasem showed at seeing Kerri and Julie.”

Just a few hours later, Jean and Liberty showed up, unhooked Kasem’s feeding tube, piled him into that white SUV, and whisked him away.

···

All this is even more undignified, of course, when you consider the kind of man Casey Kasem was in his prime. By all accounts, if you were to list the top ten things Kasem stood for—and yep, that’s exactly where I’m about to go—you’d emerge with a picture of a principled, spiritual man, albeit one with a temper. He spoke up for what he believed, whether supporting animal rights (No. 1)—he took a break from Scooby-Doo after its producers made a promo deal with Burger King—or (No. 2) trying to correct stereotypical depictions of Arabs in movies and TV. He lamented that they were seen as only “belly dancers, bombers, and billionaires.”

Yes, he would sometimes explode at work. In one profanity-laced outburst, famously caught on tape, he sounded off about how hard it was to come straight out of the Pointer Sisters’ funky “Dare Me” to deliver a dedication to a Cincinnati man who had just buried “a little dog named Snuggles.” (“They do this to me all the time,” he griped. “I don’t know what the hell they do it for, but goddammit… I want somebody to use his fuckin’ brain to not come out of a goddamn record that is, uh, that’s up-tempo, and I gotta talk about a fuckin’ dog dying.”)

But even his exasperation made him more likable. It suggested that (No. 3) Kasem had taste. Besides, while he could be cantankerous, he was (No. 4) serious about self-improvement. He’d completed Werner Erhard’s est training in 1979, and in his off-hours he preferred tapes of gurus like Tony Robbins over any kind of music. He regretted that he hadn’t been more vocal in his opposition to the Vietnam War (No. 5) and later spent considerable resources on political activism, supporting the Reverend Jackson’s two bids for president (No. 6) and championing the rights of Palestinians to claim a homeland (No. 7). For many years, he taped his show just one day a week, devoting the rest of his time to causes that included fighting for the rights of homeless people (No. 8) and opposing nuclear proliferation (No. 9). And then there were his feelings about the afterlife (No. 10): According to his Lebanese Druze heritage, Kasem believed in reincarnation.

But when his illness, diagnosed in 2007, began to erode his faculties, all that he’d built up began to break down, and the mounting rancor within the Kasem family only made his decline sadder and more poignant. As his life moved haltingly toward its conclusion, it was hard not to think about how, for four decades, Kasem had ended every show with the phrase “Keep your feet on the ground and keep reaching for the stars.” Now he was living another, much bleaker kind of countdown.

After Jean removed Casey from the Santa Monica convalescent hospital, Logan Clarke, the P.I., got a frantic call from Kerri and began the process of tracking Jean down. A few days later, one of Jean’s attorneys reported that the ailing legend was out of the country. That wasn’t true. Jean, it turned out, had driven him to what has to be the last city on earth you’d think to take a dying man: Las Vegas, where the couple, their daughter, and two caregivers occupied three suites at the Vdara Hotel & Spa, just off the Strip. (Later, in court papers, Jean would say that she’d taken Casey on “vacation” to “escape the theatrical antics of Kerri Kasem for a few days and realize some peace and privacy.”) Kasem was not examined by a physician for nearly a week.

It’s hard to imagine what Jean was thinking. Best case? She was somehow in denial about the sorry state of her husband’s health and hoped a weekend getaway would bring him happiness. The worst case: She was on the run, determined to hide his deteriorating physical condition, now exacerbated by neglect. By the time she chartered a jet to Seattle on May 13, Kasem was malnourished; according to court documents, she had attempted to feed him by pouring Ensure, a nutritional supplement, into his feeding tube. Back in California, he’d had no open wounds. Now he had a painful new bedsore on his coccyx, bigger than a saucer, and a urinary-tract infection.

When the plane landed in Seattle, an ambulance was waiting on the tarmac. The driver took one look at Kasem and presumed they were headed for the hospital. Instead, Jean asked to be taken to a private residence, a three-bedroom ranch house. The ambulance driver alerted adult protective services; bedsores can be a sign of neglect. When Clarke noticed an alert on a law-enforcement database, the mystery of Kasem’s whereabouts was solved, at least temporarily.

On May 12, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge had granted Kerri temporary conservatorship over her father’s medical care, and a week and a half later, a Washington judge upheld that order. But when Kerri headed north from Los Angeles to finally see her dad. Jean, who had hired a group of leather-clad veterans on motorcycles to protect the house, refused to let her in. Eventually, Kerri was allowed to visit her father. At Jean’s request, a judge also ordered that “photos taken of Mr. Kasem during visits shall not be disseminated.” But a few hours later, Jean did something that many saw as a far more egregious violation of her husband’s privacy: She held a press conference at which she played audio of her husband moaning. She claimed he was upset about the judge’s ruling.

“He’s crying,” Jean said, accusing the courts of trying to “rip him away from his family.”

Kerri saw it differently. “My dad was moaning because he had a bedsore bigger than the size of my hand—almost to the bone,” she told me. “He was moaning because he had a bladder infection and she had no painkillers.”

On June 1, Kerri showed up at the Seattle house with an ambulance and a team of medical personnel to transport him to a nearby hospital. As Liberty shrieked, “Where are you taking my father??” Jean came out into the yard, raised a camera to her face to chronicle the event, and called Kerri an “intrusive psycho.” Then she threw a pound of ground chuck in Kerri’s direction while muttering about “King David.” One phrase she recited over and over—”To the dogs! To the dogs!”—led some of the many, many people following this saga to speculate that she meant to liken Kasem’s kids to canine carnivores feeding on her dying husband. Or perhaps she was alluding to the Bible’s Psalm 59, attributed by some to King David? (“Deliver me from mine enemies…. Let them make a noise like a dog…. Let them wander up and down for meat.”) Only Jean Kasem could tell you for sure, and maybe not even her.

By the time Kerri got her father to St. Anthony Hospital near Seattle, he was alert but in critical condition. For the next two weeks, as the extended family gathered around Kasem’s bedside (minus Jean and Liberty, except for one short visit), Kerri and Casey’s court-appointed attorney consulted with doctors about what medical interventions were in his best interest. Not surprisingly, there was more than one document that supposedly specified Kasem’s wishes, and they conflicted. Jean argued then, and argues to this day, that Kasem would have wanted to be kept alive via artificial nutrition and hydration. But by then Kerri had won control of the decision-making, and Jean wasn’t there.

By the second week of June, attempts to hydrate Kasem were causing his lungs to fill with fluid, virtually drowning him. Soon he was removed from artificial sustenance and was given morphine to make him comfortable. Finally, on June 15, surrounded by his three eldest children and his brother, he died.

···

“Jean cut his life short,” Mouner Kasem, Casey’s younger brother, told me. “We could still have him today if she didn’t do what she did.” Casey’s health was deteriorating, to be sure, Mouner said. “But she killed him a lot quicker than he would have went.”

In the six months since Kerri hired him, Logan Clarke has made it his mission to get law enforcement to investigate Jean on charges of elder abuse. Even after months of little apparent progress, he still has high hopes, he says, that a Los Angeles Police Department probe will lead to criminal charges. “Jean Kasem killed Casey Kasem,” Clarke tells me. “And she will be arrested. You mark my words.”

That seems unlikely. Despite a December TMZ report that claimed the LAPD had submitted its investigation to the L.A. County D.A.’s elder-abuse section, the D.A.’s office told GQ that “a case has not been presented to our office” and sent us back to the LAPD, which did not respond to requests for comment.

Still, that hasn’t stopped Clarke and Kasem’s kids from trying. In the weeks after he passed, they sought to have an autopsy conducted on Kasem’s body, hoping to prove that Jean’s alleged neglect reached a criminal level. But before they could get permission, Jean sent a cavalcade of vehicles to the Tacoma funeral home where Kasem’s corpse lay: His bizarre journey, it turned out, was far from over. As was her legal right as Kasem’s spouse, Jean then removed his body and took it…well, no one knew where. For weeks, Kasem was missing. Again. Clarke started looking for him. Again.

On July 15, he got the break he needed when officials in Washington issued a death certificate that said Kasem had been sent to Montreal. A French-speaking associate of Clarke’s telephoned the Urgel Bourgie funeral home to confirm that Kasem was there. “He called the main office under an assumed identity and was able to determine that, quote-unquote, Casey Kasem is in the deep freeze,” Clarke told me.

For several weeks, Kasem’s elder kids tried to determine whether they could somehow get permission to bring their father’s body home. But before they did, a Norwegian journalist, Marcus Husby, broke the news that Kasem was on his way to yet another foreign city: Oslo. Jean had sent a letter to Norwegian authorities requesting permission to bury her husband there, claiming that Kasem “always said that Norway symbolizes peace and looks like heaven.” (His eldest kids say they don’t think he’d ever been there.) Jean also said she had Norwegian roots and that she planned to move to Norway “by the end of the year.”

Clarke says Jean’s motives are simple: She hopes to dispose of her husband’s remains outside the U.S. in order to “avoid detection of the physical damage she had done to him.” In mid-August, Kerri wrote a letter asking Norwegian officials to refuse to bury her father, saying that Kasem’s true wish was to be buried at Forest Lawn cemetery in Los Angeles, his home of fifty-three years. The letter was signed by twenty Kasem family members and friends and accompanied by a petition signed by more than 30,000 people.

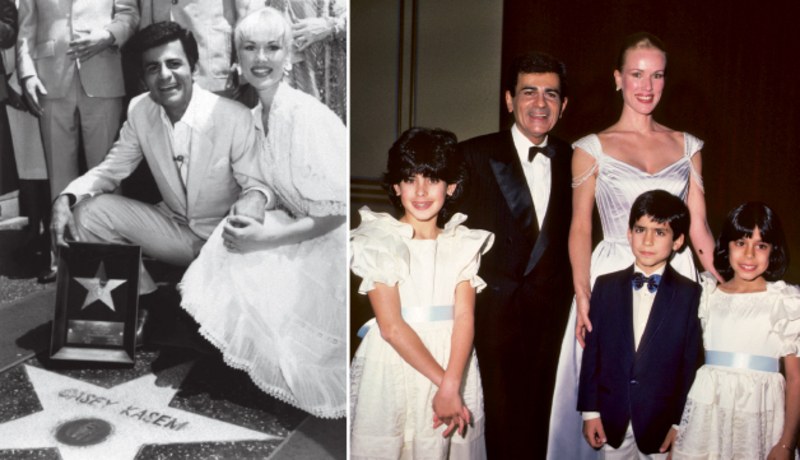

From left, Casey beaming over his Hollywood star with second wife Jan; with Jean, Kerri, Michael, and Julie at a Beverly Hills awards dinner in 1985.Photos: (from left) AP Photo: Ron Galella/ Wire Image/ Getty Images

When I first spot her, Jean Kasem does not look anything like I expected. Throughout her marriage to Kasem, when they were often photographed together on red carpets and at awards shows, her fashion sense was as eccentric as it was legendary—I Dream of Jeannie hairpieces and dreadlocked wigs, headdresses and top hats, fake flowers and sequined cleavage. By contrast, the woman who walks into a Los Angeles courtroom one Monday morning in September is a study in moneyed restraint: Her white-blonde hair is stick straight and set off by a turtleneck sweater, long skirt, boots, and Chanel spectacles—all of them black. The only flash of color is the bright red patent leather Louis Vuitton bag whose handles she clutches with one hand. With the other hand, she holds on to Liberty.

If Liberty had been born a boy, her father wanted to name her Justice, and justice is what she says she’s come to court to get. A stud in her nose and chipped purple-red nail polish on her fingers, she has the puffy eyes of a girl who’s been crying for days, and soon she’s weeping again. Mascara streaks down her face as she accuses her half siblings of neglect, religious fanaticism, murder. “They’re all Scientologists, and they killed my dad for money,” she says as her mother grips her shoulders from behind. “They had him for twenty-four hours, and they took away all food, water, and medication, and he lasted two weeks. Can you imagine?”

Kasem has been dead for months now, but the accusations Liberty is flinging are largely the same ones made in a declaration her mother filed almost a year before. In that document, Jean described the elder Kasem children as a “toxic” presence that had “irreparably shattered the lives of their father, his wife and youngest daughter.” Later she would allege that Kerri owed her father money, that she had made a living by being involved in “soft-core pornography” (apparently a reference to Kerri’s appearance in Maxim), and that as a Scientologist, she believed in “an alien warlord” and wanted to give Kasem’s fortune to the church. (Kerri denies that latter bit but will not comment on her religious beliefs, saying she’s “interested in many faiths.”)

I want to ask Jean about this, and about 600 or so other things, which is why I’ve showed up at the courthouse, at her suggestion, to finally sit down and talk. For months I’ve been asking for her side of the story. I want to hear Jean’s version of her battle with Kerri, which, at least from a legal standpoint, has been truly epic and insanely expensive: Over the past year and a half, according to court documents, Jean has gone through a remarkable thirteen different sets of attorneys. The court record reveals a pattern: She hires a firm, there’s a blast of filings, and then a few months later the lawyers ask the judge to be removed. (Jean’s current counsel did not respond to GQ’s requests for comment.)

I want to ask Jean about her alleged younger boyfriend, a Canadian named John Paul Gressy, who’d been living in the Kasems’ oceanfront Malibu condo and driving Casey’s Mercedes SUV for more than a year before Kasem died, according to Logan Clarke. And above all, I want to ask how it could ever be considered a good idea to take a very ill man who can barely speak or eat and discharge him from a convalescent hospital in the middle of the night, after disconnecting a surgically implanted feeding tube.

At one point, Jean texted me to offer “an exclusive”; another time, she addressed me, oddly, as “a colleague” and asked me to recommend a publicist. But she always stops short of an in-depth interview. Now she demurs again, citing emotional exhaustion. Later she will text me, “I have some breaking news for you if you can hang on a little longer.” And then: “I would love to participate but only if the article is truthful and accurate. If it is not a thorough article, then I must respectfully decline.” She says she might relent if I will send her a list of everyone I’ve interviewed. At that point, it’s my turn to respectfully decline.

···

Casey Kasem may be dead, but his voice lives on. In September, Kerri went on Howard Stern’s SiriusXM show, where they talked about her father, and Jean, and whom Kerri has had sex with (Corey Feldman) and whom she hasn’t (Ryan Seacrest). And in the following weeks, Stern has taken several phone calls on the air from Kasem’s corpse. Once the voice said he was calling from the Gaza Strip. Another time, he was in the tower of Big Ben, looking out over London. It was funny, sort of.

Ask Kerri and she will tell you that the saga of her father’s death isn’t just a cautionary tale about the Kasem family, or about any other rich and famous people and their troubles. Lots of families, she says, find themselves in similar situations, and she has launched a foundation called Kasem Cares to support adult children whose ability to visit and communicate with an ailing family member has been terminated or obstructed by a stepparent or other legal caretaker.

Meanwhile, everyone has been in court (of course) arguing over how much of the case’s gargantuan legal fees should be paid by Kasem’s estate. And in a separate action, the company that carried Kasem’s $4 million life-insurance policy, MetLife, has asked a judge to decide whom it should pay benefits to, since Jean, Liberty, and Casey’s elder kids are all listed as beneficiaries. Predictably, each side is challenging the other side’s right to collect.

And what of Kasem’s corpse? Throughout the fall, it remained on ice, inspiring headlines like this one from TMZ: Casey Kasem Rotting in Norway. In October, the acting head of Oslo’s burial agency told a local TV station that he was still awaiting “a clear signal” as to what to do. “I’ve never been involved in a similar case before,” the official said, “and I’ve been working in this capacity for thirty years.” There was no rush, he added: “A body can lie a long time in the freezer.”

The Kasem kids grew tired of waiting. In November, they filed court papers asking a judge to force Jean to bring their father’s remains back to U.S. soil. They were denied. Finally, just before Christmas, came word that Casey Kasem had been put to rest at the Vestre Cemetery in Oslo. His kids found out just like everyone else did: from a Norwegian news report complete with a photo of a snow-dusted grave, adorned by three wreaths. There was no headstone. Kerri immediately took to social media, saying Jean had “conned” the cemetery, and calling her “abusive” and “unfaithful.” “How many more witnesses do you need…,” she wrote in all caps. “West Los Angeles Police Department where are you?!”

The eldest Kasem children console themselves with the idea that according to their father’s Druze beliefs, he will soon be born again. As ghastly as it was to imagine his decomposing corpse, Kerri told me, “he’s not there anymore. Jean still thinks she owns his body. But he’s with us. I feel him all the time. She can’t hurt us or him ever again. Are you kidding? Lady, Dad’s with us now.”

It’s a comforting thought: the loved one finally laid to rest, not here nor there but everywhere; the countdown that never really stops. As Kasem said in his last broadcast, on July 4, 2009: Over the years, musical trends have come and gone from disco to new wave, from punk to hip-hop, from bubblegum to rock. We’ve been there, counting them down. It’s been a great thirty-nine years, and it’s really been an honor for me. But we’re not finished yet.

No comments yet.